When Indiana University professor Ellen Ketterson and Bloomington resident Eve Cusack began to discuss development of a bird banding station at IU in 2016, they saw a clear trajectory for the marriage of science and education.

A lifelong birder and amateur ornithologist, Cusack is a teacher at the Bloomington Montessori School who has worked with children ages 3 to 9 over nearly two decades in education. An educator for twice as many years working with ornithology students at IU, Ketterson is an IU Distinguished Professor and director of IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute, part of the university’s Prepared for Environmental Change Grand Challenge.

Their partnership has brought together bird enthusiasts and knowledge seekers, from infants to octogenarians, to experience wild birds, up close and personal.

Photos courtesy of IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute

The IU banding station is a part of MAPS, the international Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship program run by the Institute for Bird Populations. IU’s MAPS banding station is at Kent Farm, part of the IU Research and Teaching Preserve about seven miles east of Bloomington. The MAPS station is sponsored by the Movement Ecology working group, one of six working groups at the Environmental Resilience Institute.

Spanning nearly three decades, the MAPS program has grown to over 1,200 stations throughout nearly every state, including more than 30 stations in Indiana. Through standardized collection of longitudinal data and a software program designed specifically for the project, the MAPS program provides a vast amount of data on birds banded across North America, which can be used freely by researchers. The MAPS database, which includes more than 2 million birds, has been used as a resource in over 100 peer-reviewed papers and agency reports.

These stations are run primarily by volunteers who have a passion for birds, adventure and citizen science projects. Cusack and her husband, Sam, volunteered at several MAPS stations and other bird banding projects in the New Orleans area before moving to Bloomington as Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Their friendship with Ketterson gave them additional experience and training, as well as a banding sub-permit for Eve, leading the couple to run IU’s MAPS station.

A typical day of MAPS at Kent Farm begins with the Cusack family’s arrival at the site at dawn to open a series of 13 numbered mist nets.

“What gets me out of bed at 5:20 on Sunday mornings is the thrill of being awake when nobody else is,” said the Cusacks’ 12-year-old daughter, Dela. “It’s like going to the airport for a trip. It’s a really cool experience that a lot of people don’t have, being that close to something alive in nature that’s not a mammal. Also, my parents let me have a little coffee.”

“At the bird-banding site you can go out in nature, and you don’t have to pay for it, and it’s not an enclosed space like your yard,” added the Cusacks’ 8-year-old daughter, Nola. “I like being around birds because they’re cute and fluffy. Holding a bird is like holding a baby because you have to be delicate with it. It’s not like a baby, though, because it takes care of itself.”

The nets are checked at 40-minute intervals until 12:20 p.m. Birds are carefully removed from the nets by trained volunteers and placed gently in cotton bags for safe holding as the troop makes their way through the course and back to the station.

“It’s like being let in on a secret,” Sam Cusack said. “All around us is this amazing world that we are only peripherally aware of. Seeing the birds up close opens that world up to us.”

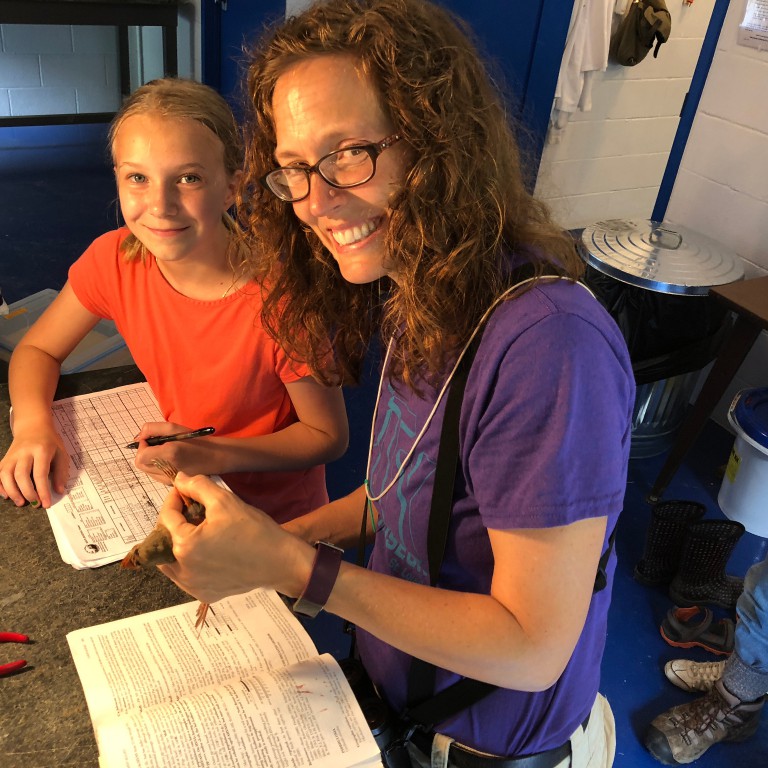

Back at the station, Eve Cusack studies the birds, one at a time, delighting in their plumages, molts and age characteristics.

Photos courtesy of IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute

First, each bird is weighed. The station’s lightest birds, prairie warblers, weigh as little as 5 grams, and the heaviest of this season, the blue jay, weighed in at 84 grams. Cusack then applies an aluminum band bearing an identification number to the bird’s right leg using specially designed pliers. This unique number allows the bird to be tracked throughout the years.

If a yellow warbler banded at Kent Farm appears in Michigan next summer, it will increase knowledge of how widely an individual bird might range from its nesting grounds. It is also one of the only methods of determining life span of songbirds. One banding-based study from Stanford University determined that a purple finch can live up to 12 years in the wild.

This information is based on consistently re-netting the same bird in order to gain longitudinal data. Scientists can also use this longitudinal data to determine changes in physical health, plumage, breeding characteristics and size of passerines, which include all songbirds that can perch.

Once the band is applied, Cusack begins a series of measurements and assessments. First, she checks the sex of the bird, which can be identified through plumage differences in many species or based upon breeding characteristics in species with identical plumage. During the breeding season, for example, male birds will have an enlarged cloacal protuberance, while females will often have a brood patch, an area on their belly where the feathers are shed and blood vessels can be seen near the surface of the skin. This brood patch allows easy transfer of heat from the mother to the eggs and nestlings.

Birds are also checked to see if they are carrying extra fat in a special cavity in the chest, a sign that they might be preparing to migrate. Then, a series of observations are made about the feather tracts on the wings and tail. Birds can often be aged more specifically by the quality of feather and whether there are observable molt limits.

Finally, Cusack measures the wingspan, which ranges from 50 to 150 millimeters on the birds commonly caught at Kent Farm. She confirms with the person recording data that all fields have been entered, and then the bird is released. The whole process can take as little as two minutes with familiar birds.

The second season of MAPS banding at Kent Farm ended in August, during which the Cusacks caught and banded more than double the number of birds they encountered in 2017. This increase may be attributable to environmental factors that led to a better-than-average summer for many types of wildlife.

“One of the most magical things about running the station is that we never know what to expect,” Eve Cusack said. “After 10 banding sessions in summer of 2017, our largest count in one day was around 20. In 2018, we banded 36 birds in our first session, and the numbers just went up from there.”

At times, the Cusacks will find five or six birds waiting to be removed from a single net. Once, two male red-bellied woodpeckers who had landed close to each other were sounding their piercing alarm calls as the Cusacks worked in tandem to remove them quickly. The sound was deafening.

In completing their second season, the Cusacks and other station volunteers have learned a lot about the bird populations in southern Indiana. They have banded 37 species of birds, totaling 340 individuals, and recaptured 90 birds that they had previously banded, adding to one of the only sources of longitudinal data about birds available to scientists around the globe.

The only thing Cusack said she enjoys more than the banding and examination of the birds is sharing that process with children and other visitors.

A frequent volunteer, Judy Klein, said that MAPS has “opened up a multidimensional world of sight and sound for me,” and calls her time at the station “an unexpected joy and revelation.”

Since 2016, the Cusacks have also hosted several guests from the IU Foundation, three local composers, local authors, professors, teachers, documentary filmmakers, doctors, retirees and many children. These guests from different backgrounds have gained a new lens through which to view the natural world.

At the least, Cusack said, they’ve seen the precious gifts nature has created all around us, and at best, they’re inspired to do all they can to promote the well-being of our planet’s living things. A visit to a MAPS station can truly be a life changing experience, she said.

The collaboration between the Cusacks and the Kent Farm Research Station was brought about by Prepared for Environmental Change, one of three initiatives funded through IU’s Grand Challenges Program. This initiative created the Environmental Resilience Institute, whose mission is to predict the impact of environmental changes and develop solutions that prepare Indiana businesses, farmers, communities and individuals for that impact. The Environmental Resilience Institute aims to accomplish its goals through the collaboration of its six working groups.

Allison Byrd is a research associate in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Biology. Eve Cusack is a teacher at the Bloomington Montessori School. Ellen Ketterson is an IU Distinguished Professor and director of IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute.