When Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 was passed, the intent was to address sex discrimination and provide equal access to education and employment opportunities for women. Fifty years later, the scope of the legislation is far-reaching, playing a role in academics, athletics and the handling of sexual violence at federally funded educational institutions.

The origins of Title IX

Indiana University alumnus and former U.S. Sen. Birch Bayh is known as the “father” of Title IX due to his work as a sponsor and co-author. Bayh had two co-authors in the House: Rep. Edith Green from Oregon and Rep. Patsy Takemoto Mink from Hawaii.

Mink was the first Asian American woman to serve in Congress and graduated from the University of Chicago Law School after being turned down from attending medical school. She was still serving in Congress when she died in 2002, and at that point Title IX was officially named in her honor.

Bayh had said he was inspired to help champion the issue, in part, by his first wife, Marvella. A straight-A student and president of the student body, she wanted to attend the University of Virginia. When the response to her application arrived, it said “Women need not apply.”

“That was the first taste of discrimination she had ever experienced,” Bayh said in an oral history interview with IU Bloomington Professor Emerita of Law Julia Lamber. “It had a profound impact on her.”

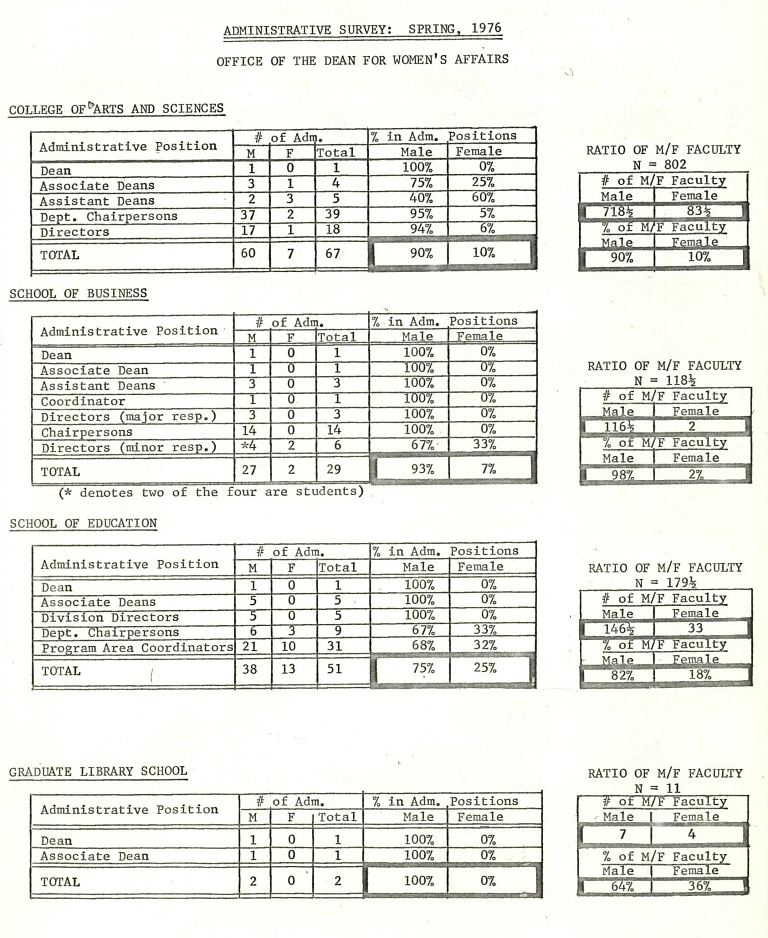

Bayh wanted to ensure other women didn’t face the same obstacles in pursuing their dreams. In remarks he made about the need for legislation addressing sex discrimination, he discussed how it bled into several aspects of education, including admissions, scholarships, faculty hiring and promotion, and professional staffing pay scales.

A fact sheet from Bayh’s congressional office outlined some of the disparities, showing that in 1968-69, 96 percent of the degrees conferred by professional schools went to men. Statistics also showed that men occupied the highest faculty ranks, while most women were stuck at the instructor level and below.

Bayh tried multiple ways to pass legislation addressing discrimination against women in education, and ultimately found success in 1972. President Richard Nixon signed Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 into law on June 23.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance,” Title IX reads.

The legislation is administrated by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, which is a governmental body in the executive branch. It had to set policy before Title IX could be enforced, so it took years for the law to be fully implemented. Its impact is broad.

“Sex discrimination has been interpreted to include sex-based harassment, discrimination, unequal opportunity,” said Jennifer Drobac, the Samuel R. Rosen Professor of Law in the IU Robert H. McKinney School of Law at IUPUI. “Even if you’re not completely banning someone from entering the school gates, but if you’re making it really hard because they’re subject to name calling, bullying on the basis of sex, sexual assault, or even just hostile behavior – ‘girls don’t belong, girls aren’t good at math and science’ – that’s where all of this is going to apply.”

And how the law is applied continues to evolve.

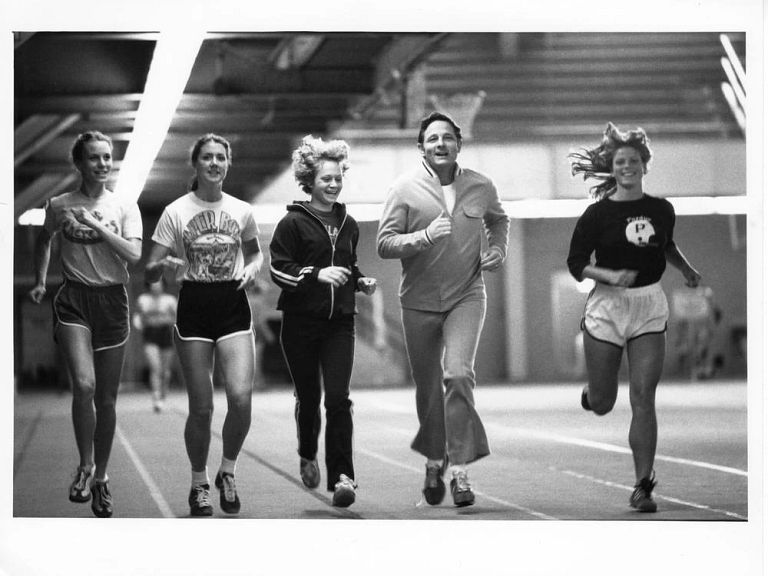

Equal opportunity in athletics

While Title IX makes no reference to athletics, its potential impact on college sports garnered lots of attention during discussions about regulations that would carry out the intent of the law.

“You heard from especially the football coaches who were scared that all of a sudden their programs were going to be eviscerated or, at best, impaired,” said Jayma Meyer, a visiting clinical professor in the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs who specializes in Title IX.

In his oral history interview, Bayh described a meeting he had with Notre Dame football coach Moose Krause, during which Krause claimed Title IX would destroy the program.

“I said, ‘Help me understand. I’ve read this piece of legislation several times, and where does this mean that the next time you play in a bowl game that your adversary is going to have 12 men on field and you’re going to have only 11?’” Bayh said.

Several amendments were proposed in an attempt to address concerns about Title IX’s effects on revenue-producing sports like football and basketball. The Department of Health, Education and Welfare issued a policy interpretation on Title IX and athletics in 1979. Among other things, it established tests to determine whether institutions were complying with Title IX.

“First, the test requires equitable opportunities between men and women to participate in sports – with two defenses,” Meyer said. “It’s not the same number of teams; it’s the same number of opportunities to play. So, if men’s football has 120 players, that number along with all the other male slots has to be equalized in the women’s athletics program – based on a formula that considers the percentage of males and females enrolled at the school.”

Second, the policy requires federally funded schools to provide equal financial aid. And, third, it requires equitable benefits and treatment to male and female athletes.

“So here too, in a nutshell, if 120 football players receive a certain kind of benefit or treatment, so too must that many women receive an equivalent benefit or treatment,” Meyer said.

According to the Women’s Sports Foundation, women made up 44 percent of all NCAA athletes in 2020-21, compared to just 15 percent before Title IX. But the number of athletics opportunities available remains disproportionate to the number of women enrolled in college.

Protection against sexual harassment and violence

Under Title IX, sexual harassment and sexual assault are also considered forms of sex discrimination and prohibited under the law.

Shortly after Title IX passed, what was known as IU’s Office of Women’s Affairs at the time received a grant from the U.S. Department of Education to create the first video on sexual harassment on college campuses. “You Are the Game” increased awareness by showing students in several situations experiencing different forms of harassment, followed by a panel discussion. The Office of Women’s Affairs also conducted one of the first national surveys on sexual assault and harassment policies at higher education institutions.

How Title IX applies to sexual misconduct at universities has changed several times since then, often based on who is in the White House.

“While Title IX law itself can’t be changed without congressional approval, there have been guidelines, letters, guidance and a variety of other documents of a more informal nature that have come out of the Office of Civil Rights which basically implemented different standards and guidance that schools then followed,” Drobac said.

The most recent regulations introduced in 2020 reiterate that Title IX applies to complaints of sexual harassment, sexual assault, dating or domestic violence, or stalking. For the Title IX process to govern the complaint and investigation process, those incidents must have occurred on campus or within a university program or activity in the U.S., and the complainant and the respondent must be a current student or employee, or have a current affiliation with the university. If any one of those factors is missing, the university may still address the behavior in the university’s sexual misconduct investigation process. The two procedures are similar, with both striving to provide an equitable process and outcome for the parties.

IU’s Stop Sexual Violence website includes information about how to report incidents of sexual misconduct on IU’s campuses, as well as resources for employees and students. Confidential victim advocates are available to help people through the process.

“The confidential victim advocate is someone you can have with you throughout the process that you can talk to at any time,” said Jennifer Kincaid, IU’s director of institutional equity and Title IX coordinator. “I’ve known times where they’ve sat overnight at the emergency room with individuals. They can go to their meeting with the investigator with them. Just to have someone accompany you throughout that is so valuable.”

The intricacies of Title IX are complicated, and Kincaid said the process that takes place when a sexual misconduct complaint is filed depends on multiple factors. The university tries to honor the wishes of the person filing the complaint when possible. In some cases, that person might only want to be connected to support resources.

Complainants are also informed about how to make a report to law enforcement if they wish. It does not mean that the prosecutor will end up filing charges, however, as the criminal code has different definitions and standards of proof. Title IX only covers school and university responsibilities.

The university is also required to report criminal behavior under the federal Clery Act, even if a complainant does not want to go through the law enforcement process.

“There’s so much care and attention and thought by a lot of people put into every situation and every step, and trying to both do it the right way and be compliant with the law,” Kincaid said.

Drobac said the current Title IX sexual harassment standard can be tough to meet. It also makes it more difficult for a student to demonstrate a violation than an employee, who would also have protections under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which defines sexual harassment differently.

“The complainant has to prove under the Department of Education standards set by Betsy DeVos ‘severe and pervasive harassment,’” she said.

Even if that standard is met, that doesn’t mean the issue will be addressed through criminal courts. Drobac said cases can be referred to the police or prosecutor, but Title IX deals with, at most, disciplinary action by a school.

More changes are likely on the horizon for how universities comply with Title IX. In June 2021, following the Supreme Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, the Department of Education confirmed that the Title IX prohibition on sex discrimination encompassed discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The Biden administration is expected to release new Title IX regulations in June of this year which may enshrine that provision in the regulations and also include other changes.