For Indiana University laboratory biologist Dan Tracey – who set sail Feb. 1 to study the evolution of genetically isolated fruit flies on the volcanic islands of the Lesser Antilles – the chance to collect data on these insects during a months-long sea-faring adventure is both a scientifically significant endeavor and the realization of a longtime dream.

Growing up near Buffalo, New York, Tracey grew up sailing with his father on Lake Erie. Being out on the water on their boat was a large part of their life together. But it wasn’t until Tracey’s father passed away from cancer last year that he started to seriously think about turning his dream research mission – which he often talked about with his father – into a reality.

“I started thinking, ‘What would I do if I could do anything I want?’” said Tracey, a professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Biology and a Gill Chair in the Linda and Jack Gill Center for Biomolecular Science. “What would my dream research project be?”

With support from Jack M. and Linda Gill of Texas, whose generous gift to IU established the Gill Center in 1999, Tracey is retracing the steps of William B. Heed, a well-known biologist who conducted a similar expedition in the Caribbean in 1959.

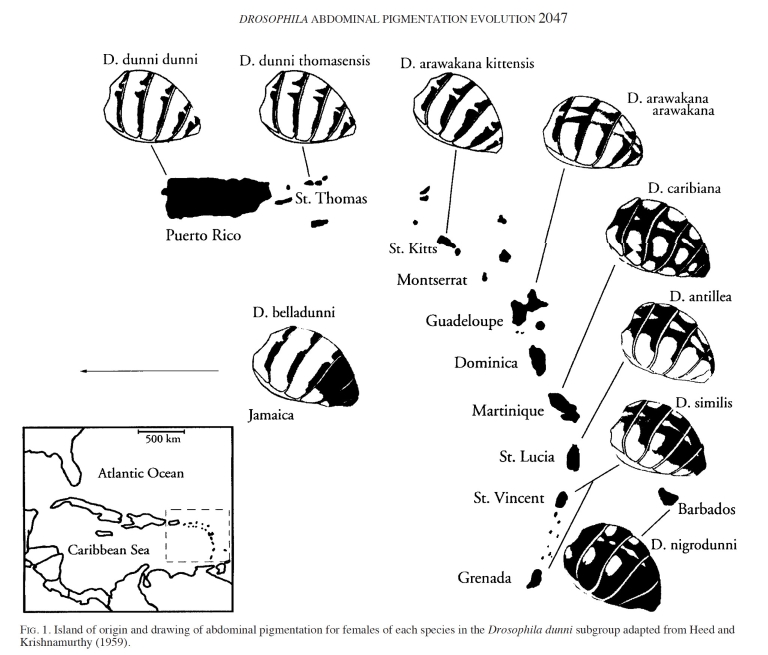

Heed traveled the Lesser Antilles and discovered that the fruit flies on each island differed in pigmentation.

Tracey is now eager to discover what the evolution of this pigmentation means.

Tracey and two others are currently sailing from the south to the north of the Caribbean, stopping at 11 islands along the way: Grenada, St. Vincent, St. Lucia, Martinique, Dominica, Guadeloupe, Montserrat, St. Kitts, Antigua, Anguilla and St. Martin, where the journey ends May 1. During the voyage, the crew are working and living aboard a 41-foot rented catamaran named “Sea Salt.”

On each island, Tracey and colleagues are spending about a week collecting Drosophila, the Latin name for fruit fly. They will later store and genetically analyze the insects at IU to trace the origins of their pigmentation.

“These species have different patterns of pigmentation, with the darkest pigmentation in the most southern species and the least pigmentation in the most northern species,” said Tracey, who uses fruit flies as a model species in research on the genetic origins of pain sensation. “No one exactly knows what this difference means, but I think it’s related to parasitoid wasps.”

The evolutionary tug-of-war between fruit flies and parasitoid wasps – which reproduce by injecting their eggs into the flies’ larvae – has long been studied by biologists, Tracey said. He hypothesizes that pigmentation may indicate a fly’s ability to defend against parasitoid wasps, since melanization plays a key role in one of the many defense mechanisms evolved by Drosophila to protect against their aggressors: an immune response that “walls off” the eggs inside the larvae so they’re unable to feed upon the larvae after hatching.

If parasitoid wasps are found on the journey, it could shed new light on the co-evolution of these insects. The volcanic origin of each island also represents the chance to study these evolutionary systems isolated from outside influences.

Tracey will be accompanied on his journey by Jeremy Davis, an IU Ph.D. student with extensive experience capturing Drosophila in the field. In 2016, Davis spent six weeks traveling across the United States collecting fruit flies under a grant from the Graduate and Professional Student Government’s Research Awards program.

That project took him from “city parks in New Orleans to the bayou, the mountains and dried-up riverbeds,” he said. The experience not only gave him a good eye for finding flies but gave him experience capturing them.

Davis is a member of the lab of IU biology professor Leonie Moyle, who recommended him for Tracey’s project because of his experience in the field.

“It sounded like a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” Davis said. “I’m very excited about the science aspect of the trip, as well as traveling and learning to sail.”

The third member of the team is Amalia Rowan, an experienced sailor who is working toward the next level of her captain’s license. Rowan has worked on Alaskan fishing vessels and, most recently, sailed across the Atlantic in a small ship.

But it wasn’t until a few weeks ago in Miami that all three members of the crew finally met in person, after which they took a short flight to Grenada to join their boat and equipment. The team is currently spending their days hiking the islands, setting up fly traps and searching for wasps.

“The truth is we still don’t know a lot about these species because no one has looked in a long time,” Tracey said. “That’s why we’ve got to go there and do it.”

To follow Tracey’s fly-hunting adventures this semester aboard “Sea Salt,” follow him on Twitter at @HoosierFlyMan.