BLOOMINGTON, Ind. – Populations of the Gulf killifish have evolved over the past 50 years to live in water with toxin levels that are deadly to most other species. An interdisciplinary team of researchers – including an Indiana University environmental toxicologist – have found that DNA acquired from another species explains why.

Joseph Shaw, a scientist at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, was part of a research group led by Baylor University and University of California, Davis, that describes how Gulf killifish living in the Houston Ship Channel rapidly evolved pollution tolerance in a study released today in Science.

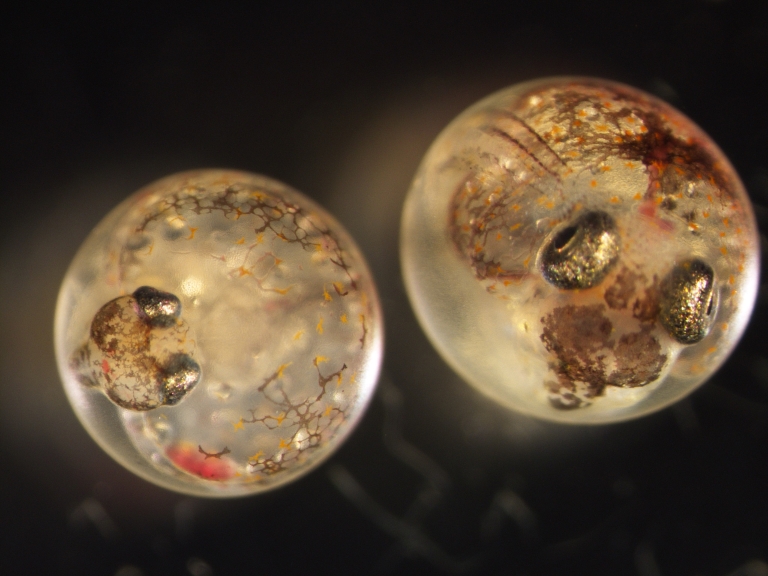

The minnow-like Gulf killifish are an important part of the food web for a number of larger fish species in coastal marsh habitats. Shaw has spent years studying how they change in response to their environment, research that will help predict and prepare for global climate change.

“Studying how killifish are able to live in these toxic conditions provides important lessons that can be critical for preserving biodiversity in the face of rapid environmental change,” Shaw said. “In this case, we learned that what worked for these fish likely will not work for others.”

The team studied the genomes of Gulf killifish across a large pollution gradient – from fish living in pristine water near the Gulf of Mexico to those living in highly polluted water in the heart of the shipping channel near Houston. Despite massive populations that allow them to maintain high levels of genetic diversity, killifish needed even more of a genetic boost to bolster their resistance to toxicity.

The researchers found that DNA from a distant relative – a species of killifish that lives more than 1,000 miles away on the Atlantic coast and has also been shown to evolve pollution tolerance – rescued the Gulf killifish. The research team suspects humans accidentally played a role in bringing the Atlantic invader to Texas.

Invasive species, usually known for the environmental destruction they cause, provided the required genetic variation at exactly the right moment to allow the Gulf killifish to survive high levels of chemical pollution – a process known as evolutionary rescue.

The conclusion is one of caution, because most species cannot cope with such rapid and dramatic environmental change. A unique set of circumstances – including huge population sizes and a chance encounter with a distant relative — allowed the Gulf killifish to survive as its habitat was destroyed by chemical pollution.

“Success for most other species will require humans to reduce the pace at which we are altering the environment,” Shaw said.

Co-authors from the University of Connecticut also contributed to the article.

The work was supported by funding from a C. Gus Glasscock Endowed Research Fellowship, Baylor University, the Exxon-Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences and IU.

This study reflects IU’s extensive expertise and research regarding biology, law, media and the environment. To build on the intersection of these areas of core strength, IU President Michael A. McRobbie, along with several community partners, announced in May 2017 the Indiana University Prepared for Environmental Change Grand Challenge initiative.